Maeley Tom’s Book Explains Who She Is—To The Reader and to Her

A governmental dynamo graciously shares her life story

By Ed Goldman

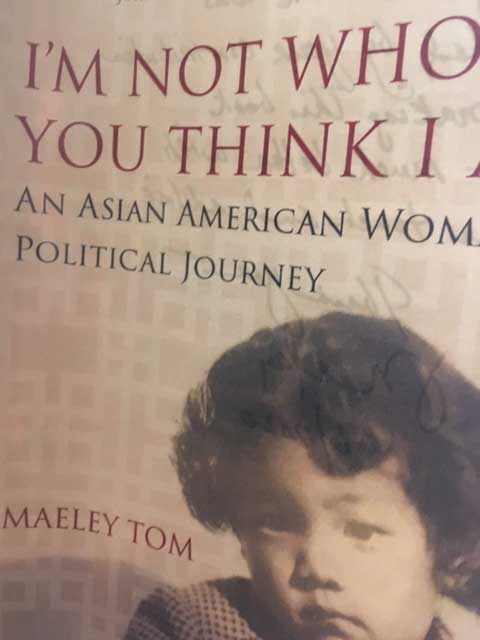

First, it’s very easy for me to tell you my opinion of Maeley Tom’s new book, “I’m Not Who You Think I Am—An Asian-American Woman’s Journey,” because it’s right there in the book’s opening pages of rave reviews.

After reading and making a few suggestions on the manuscript months before the book was published, I called it “a clear-eyed but touching memoir, a guide book on how the inner workings of government in the country’s most progressive state grind along” and “an awesome, very human achievement.”

So, if there are no further questions… .

Actually, Tom’s book, available at Amazon, is an emotional ride, even though she keeps much of the sentimentality in check. From her unique origins in San Francisco as the child of celebrities in the insular world of Chinese opera—”a lost art,” she tells me with a tinge of regret in a recent interview, “that has faded, both here and in China, though I hear there’s been a revival in Canton”—to being foster-parented by a wonderful woman (in a wonderfully rendered portrait) she refers to as Mama, to embracing the independence that had been forced on her, Tom presents a matter-of-fact account of a life rich with cinematic scope.

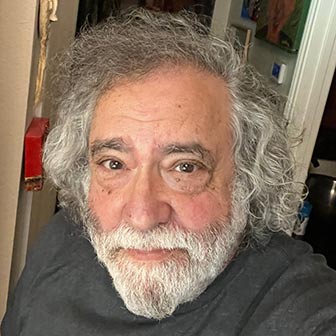

Through it all, you can’t shake the image of her on the cover of her book: a round-faced, very somber little girl who wouldn’t know until later in life how much her father and mother loved her in very non-traditional ways. As you should be able to tell by the other photo accompanying this column, Tom grew into a vibrant, upbeat doer, with a 50-year marriage to pharmacist and now-retired lobbyist Ron Tom; a talented daughter, Stephanie, who heads the department in charge of broadband for the State of California; and a grandson, Maxwell. If you spend any time with Tom, or just watch her walk across a restaurant, the combo of her energy, humor and personal style will have you shaking your head in disbelief at her age, which she volunteers without a moment of hesitation: 78.

One of the oddest memories Tom has of her mother, a tough-as-nails woman whom we’d call “withholding” in modern therapeutic jargon, was when Tom’s daughter was born and the new grandma took her from street to street in a colorful Chinese-American enclave of New York city to show her off. But it wasn’t strictly from pride and joy, Tom says. “The gamblers and businesspeople who lived there handed my mom gifts of cash. It was a tradition.” I think to ask Tom if her mother then gave her the cash, based on another story she had told me about the older woman regularly misspending checks the Toms had given her for living expenses and medication as she grew older. But I let it slide when Tom then tells me about the time she finally gave her mom hell for being absent all the time and “a truly terrible mother. I couldn’t believe I was saying all of this. it just wasn’t my nature to vent like that.”

Maeley Tom today (photo by Tiffanie Yee)

Here’s how she writes about her mother when she was dying. The old woman had just complained about Tom and compared her unfavorably with the daughters of her friends, prompting an outburst from Tom—one she’d kept bottled up for most of her life:

“…I remember (she lay) expressionless and silently on the bed as I screamed at her, as if she was listening to me for the first time. After a moment of awkward silence, with me sobbing uncontrollably, she said in Chinese, with a deadpan face, ‘Well, at least I see you inherited my temper.’ It totally stopped me and I burst out laughing because at that moment I realized for better or worse, this was my mother; this was simply who she is.

“That release of my lifelong repressed anger and emotion toward my mother freed me to finally be able to love her for who she was. I climbed back on the bed with her, laughing and crying at the same time to cherish that rare moment of us holding on to each other as mother and daughter as I whispered to her ‘I love you mom’ and really meant it. This was the first time I saw my mom cry.

“I only wish she had said the words ‘I love you too.’”

The cover of Maeley Tom’s memoir

Tom says the part of her book dealing with her mother so concerned “a Chinese multimillionaire” acquaintance that “he felt compelled to contact me and say, ‘I know what made your mother tick. It wasn’t her fault. Her life was hard and she did the best she could.’” In fact, Tom is wonderfully circumspect and even empathetic about both of her parents, who were unfaithful to each other for years—Tom thinks her mother became that way because she found out her father had strayed, repeatedly—and eventually divorced. Later in her dad’s life he and Tom grew close for a time.

With all of what Tom learned and the contacts she made—in a career that included being the first woman to become chief administrative officer of the California Assembly, as well as the first “ethnic minority woman” (her term) to become chief of staff to the California Senate pro tem—it’s surprising that she never ran for office herself. She was what’s now called “crazy-smart,” knew where all the bodies were buried, and was not only attractive but also married to a man she said “was movie-star handsome in those days” (in my opinion, Ron Tom—tall, trim and elegant in his early 80s—still has more presence than even Governor Gavin Newsom could hope for).

“Oh, I was approached but I was just a chicken,” Tom says, laughing. “Besides, helping other Asian women learn how policy and politics work is much more fun.”

She captures that in the closing words of her book:

“And my greatest gift to myself,” she concludes, “is finally accepting who I am today. And now, maybe you, too, know who I am.”

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).