Seven Days a Week, People Love Four-Day Workweeks

What will this mean for the expression TGIF?

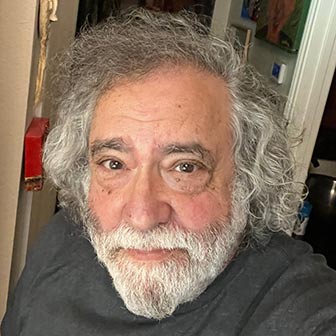

By Ed Goldman

More than 60 British companies confirm that giving employees a four/day workweek—but pretty much demanding that in those four days they accomplish as much as they did in five days—has been a resounding success.

To verify the finding, yesterday afternoon I tried to call some British friends with whom I’ve stayed in touch over the years. But they’d either left already for the weekend or, to my surprise, not begun their workweek as yet.

On-and-off-boarding

I guess the four-day workweek isn’t the same for everyone.

Under the plan, a majority of employees take Fridays off, while others opt to skip Mondays instead. The ones who shed a midweek day are just too irritating to worry about.

Even worse are the jokers who take alternate days off in alternate weeks—say, Tuesdays during the first week of the month; Wednesdays in the second week, and Thursdays the third. I’m sure most supervisors—and possibly even HR managers—would agree with my opinion that those people have a special place in Hell awaiting them.

SUPERVISOR: So, Harold, good to see you back in the office. Missed you on Friday.

HAROLD: Thanks. But I’m only here for today. I’m taking Tuesday off this week.

SUPERVISOR: Tuesday?! You mean, like, tomorrow?

HAROLD: Well, there’s only one Tuesday in the week, Boss.

SUPERVISOR (Sighing): So far.

About 20+ years ago, the State of California experimented with “flex” schedules for employees in most of its innumerable departments. The running joke at the time was, “How will the public be able to tell the difference?” It wasn’t so much that state employees weren’t at their posts during the workweek; it was that while there they accomplished very little.

That perception held (and holds) true for a number of government workers, whether employed by the city, county, state, community district, township or burg. Unless the employees are public safety workers—cops, firefighters, doctors, nurses, DAs, for example—chances are they work in offices. And these days, a plurality of them work “from” home, as they say, rather than “at” home. “From” evidently sounds more dynamic, as though, sure, they may be wearing pajama bottoms, sweatshirts and Uggs all day, but give them a real emergency—like a wildfire to write memos about or the printer needing toner—and they’ll be up and at ’em before you can say “Compensatory Time Off for after-hours work.”

In my peculiar line of work, schedules are highly elastic things. (I believe that in Ethiopia, they used to be known as Hailey Selassie things.) With the exception of showing up for interviews and meeting deadlines when I write for editors far more demanding than the one at The Goldman State—c’est moi, c’est moi, I’m forced to admit—I set my own work schedule. It goes something like this:

Monday: Read and write, 8-10 a.m. Brunch at 10:30 a.m. Soup or celery sticks at 3. Read and write. Dinner at 8. Cocktail, local news, Colbert’s monologue, watch old movies until 1 a.m.

Tuesday-through-Thursday: See Monday.

Friday: See Monday-through-Thursday but add tape Bill Maher before watch old movies.

Saturday-Sunday: Do crossword puzzles, visit art exhibits, eat like a deprived timber-wolf at least twice each day.

Some traditional office banter will of course suffer from the global acceptance of the four-day workweek.

For example, those routine, urbane hallway exchanges—such as, “How’s undeniable sparkle since “Tuesday” may no longer seem the burdensome day it’s always been when facing a few more days of drudgery before the weekend.

Which is to say, “Tuesday” may be someone’s new Friday. As a result, that person may respond to the inquiry of “How’s it goin’?” by joyously declaring, “Thank God it’s Tuesday!”

This also begs the question of what will happen to the beloved bar-and-restaurant-and-bar-and-bar chain, TGI Fridays. Will it have to change its name to TGI Whenever? If that occurs, I fear for the future of the Commonwealth! (Not really. I’ve just always wanted to us that expression in an essay—and since it’s unlikely I’ll be asked to write opinion pieces for The Economist anytime soon, I thought I’d get it out of my system.)

Finally, the four-day workweek issue reminded me that in the early 1970s I worked for two days at an advertising agency in Newport Beach called Lansdale Carr & Baum—which, in addition to having an impressive roster of clients, also owned a retail business of its own: 4Day Tires.

The gimmick was that the store would be open only four days a week (Wednesday-through-Saturday, as I recall). The firm did this in recognition of the peak days customers actually bought tires—it had the market research to prove it—and to pay fewer employees and incur less overhead.

To test my copywriting skills, agency partner Phil Lansdale, whom I really liked—on my first day he bought me my first-ever two-martini lunch (I had just turned 22)—gave me a stack of statistical data about tires. Each Saturday, the firm ran a full-page ad in various newspapers that consisted entirely of several hundred words about tires. My job was to take a crack at writing one.

I fought tedium (and the effects of that two-martini lunch) as I pored over the verbiage about the amazing world of tires, coming up with a saga I’ve long forgotten about myths of the invention of the wheel.

My reward, once Phil took his blue pencil to it, was that 4Day Tires would be my exclusive account at the agency. Not the entertainment personalities, the fashion design firms, the TV stations and the magazines they repped. No, my glam client was to be an offshoot of the rubber industry.

I tactfully tendered my resignation to Phil on Day 2—by phone. I figured, why get up early and drive 20 minutes to tell someone I wasn’t going to be in that day?

In so doing, I may have created the two-day week. The pay’s lousy but the hours are great.

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).