Calling A Spay A Spay: Trouble In River City’s Animal Shelter

In the first of a two-part column, we discuss problems of the four-legged homeless in California’s capital

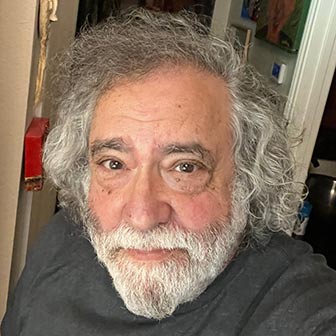

By Ed Goldman

My city, like too many cities, has challenges with homelessness.

In my columns for today and Wednesday, I’m focusing on the four-legged victims of homelessness—because it’s a far more immediately solvable problem than the kind afflicting the two-legged ones.

Julie Virga with Bandit, rescued from a no-kill sanctuary after he’d been there 6 years.

Unlike their human counterparts, cats and dogs that are homeless and die premature deaths don’t do so because of mental health issues, lifestyle choices, drug or alcohol use, social stratification or the vagaries of the economy.

Let’s begin by offering a thesis statement: The City of Sacramento’s Front Street Animal Shelter used to be seen as a model of how to run one of these. Today, management of the facility is seen as a shamble of laziness, bureaucratic indifference and lack of accountability.

Now, let’s meet the players.

We have Phillip Zimmerman, who had some experience managing an animal shelter in Stockton before he landed his current job running the City of Sacramento’s. His boss in Sacramento is a fellow named Tom Pace. Pace is Sacramento’s director of community development and for some reason, his job duties include being responsible for the shelter. Of note is that he used to be the deputy community development director for planning and engineering at the City of Stockton, “responsible for advance and current planning, design review, historic preservation, environmental impact review, development engineering, encroachment permits, assessment districts and infrastructure finance, and flood control planning,” according to his online profile.

I’m not sure that managing the manager of an animal shelter would have been on his list of “other duties as assigned.”

Another player is City Manager Howard Chan, a fond acquaintance of mine from his days as head of the city’s parking division, whom Zimmerman and Pace ultimately answer to. Chan told Julie Virga, a local animal activist, that he would order an audit of Sacramento’s Front Street Shelter’s operations only if a member of the Sacramento City Council requested it. Five months after she indicated she would do so, Vice Mayor Angelique Ashby, at the time in a neck-and-neck race to become the state senator from her region—she declared victory last week—made the request. It will be done in late spring of 2023.

But Ashby won’t be there to make sure it gets done. She’ll be in the State Capitol. And a lot of animals will die by then.

Of passing interest, a few days after Ashby asked for the audit, Chan—breaking protocol, tradition and maybe just positive optics—endorsed the candidacy of Ashby, one of his nine bosses, for the Senate—and a few days later, eight of the nine city council members voted to bump Chan’s salary to more than $400,000 per year, making him the second highest paid city manager in California.

If the timing seemed questionable but possibly unconnected, this stat didn’t help: “Sacramento experienced 58 homicides in 2021 compared to 44 homicides in 2020, according to police. In 2006, Sacramento recorded 59 homicides, which is the highest number of homicides in the last 16 years,” according to a report on KTXL, Sacramento’s Fox News affiliate.

Statistics like these aren’t exactly praiseworthy—though apparently raise-worthy. The city manager of Sacramento hires the police chief, who in turn answers to him. (“Heckuva job,” as W said to FEMA Director Michael Brown the fellow overseeing the agency’s rather disastrous handling of Hurricane Katrina a little more than seventeen years ago.)

A few months ago, Hilary Bagley-Franzoia, a retired Sacramento County animal-cruelty prosecutor, wrote a lengthy, detailed letter to Chan to express her concerns about the shelter.

“After prosecuting animal abuse cases throughout my 30-year career,” she wrote, “…I am writing you about what I believe is the continuing mismanagement of the City shelter, in terms of questionable fiscal practices and the inhumane treatment of animals.”

Hilary Bagley-Franzoia with Teddy, rescued from a crack house.

She continued: “Following a trendy model that places the onus of caring for abandoned animals on members of the community rather than with the public (and publicly paid) officials whose jobs are to provide safe and reliable care for our beloved cats and dogs, Front Street has largely abrogated any sense of moral authority in the name of expedience… .”

That “trendy model” is known as the Koret Model. Please read on:

“Recently,” Bagley-Franzoia’s letter explained, “California Governor Gavin Newsom allocated $50 million to make California a ‘No Kill’ state, as well as to reduce the number of animals entering our shelters. The reduction of intake would of course reduce the number of shelter euthanasia procedures performed.

“Yet while saving animals is a well-intentioned endeavor, the governor assigned the monies to the Koret Shelter Medicine Department located within—but allegedly neither officially affiliated with nor funded by—UC Davis. The stated purpose was to develop programs and administer grants to achieve his goals. The hope among animal advocates was that this allocation would enormously increase spay and neuter efforts throughout our state.”

It hasn’t exactly worked out that way, as discovered by Bagley-Franzoia and her fellow animal activists, including the aforementioned Julie Virga, a businesswoman whose late father and brother were Sacramento judges. It’s Virga who contacted me months ago to ask if I’d write about the shelter. I had never met her before; this factoid will have some resonance in the second part of this column, which will run Wednesday.

“Unfortunately…, reducing the number of surplus litters in our community does not appear to be the primary direction of the Koret department,” Bagley-Franzoia’s letter continued. “To satisfy the governor’s goals, Koret launched a ‘Capacity for Care’ model … that offers a series of grants to entice California animal shelters to implement it.

“But this is a model that induces reduced intake simply by turning away community animals in need. The Koret model is merely a better-funded version of the HASS (Human Animal Support Services) ‘Community Sheltering” model,’ which has failed in numerous shelters in the United States (El Paso, Texas, was a prime example of this).”

As with many failures, the COVID-19 pandemic makes more than a cameo appearance in this scenario as the all-purpose scapegoat for the shelter’s management simply sloughing off. (Presumably, blaming the blocked supply chain, gas shortage and Hunter Biden’s laptop seemed too much of a stretch.)

In Wednesday’s column, we’ll take a closer look at the shelter. In the meantime please pet the four-legged animal on your lap. All he or she asks is for comfort and safety.

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).