Neither a Pandemic Nor Cancer Stops Jennifer Stolo From Wish-Granting

Make-A-Wish Foundation leader is a true life force

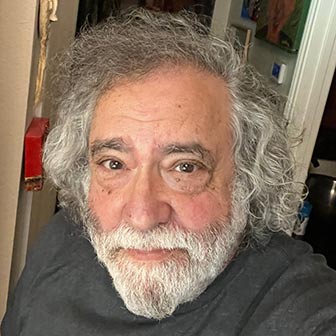

By Ed Goldman

Cancer messed with the wrong lady,” says Jennifer Stolo, the kinetic president and chief executive officer of the Make-A-Wish branches of Northeastern and Central California, as well as Northern Nevada.

“People call me a cancer survivor or a cancer warrior,” she says. “But my sister Kelly, who’s also my best friend, said those titles just didn’t work. She said, ‘Jen, you’re a cancer ass-kicker.’” Stolo offers her cheerleader grin: radiant enough to be seen from the top of the bleachers. After a slight pause, she says, “And yes, I’m going with that: cancer ass-kicker.”

Empathy is hardly a new trait for someone who’s spent the past eight-and-a-half years helping grant the fervent—and tragically, sometimes final—wishes of thousands of seriously ill children, ranging from two-and-a-half years old all the way up to 18. But this past spring, doctors discovered she, too, was ailing. She had breast cancer.

“Because of COVID, we were just starting to appreciate here, on a whole new level, what our clients’ parents go through, making sure the environment at home is always sterile, wiping everything down regularly to accommodate compromised immune systems,” she tells me in a recent Zoom call. “So here are my staff and me. We’re working from home, being safe. We’re learning to walk in the shoes of the parents as well as the kids.

“And then this happens.”

Stolo says “this happens” without sighing, rolling her eyes or showing the least bit of self-pity. To her, it seems more an episode in the continuing narrative of her life than a permanent setback. Before coming to Sacramento and Make-A-Wish, she’d already established a reputation for excellence (and relentless energy) in nonprofit management. She had worked for a decade in early-childhood education, then moved to Boys Town, the famous facility for at-risk young people. (How famous? Spencer Tracy won an Oscar for portraying its founder, Father Edward Flannagan, in a 1938 film of that title.) Stolo was at the institution’s southern California branch, not the place’s original base in Omaha, Nebraska.

Her next gig was with the California Dental Association—but lest you think she’d moved from the field of caring into trade-group marketing, her job was to manage a $40 million statewide campaign to expand access to dental care, including pediatric oral healthcare and fluoridation initiatives. The latter were and remain somewhat controversial, with some non-scientists still embracing the notion that fluoridation is a communist plot—though to this day, I have no idea how creating generations of cavity-free children would abet the cause of socialism. But I digress.

Stolo oversees a staff of 25 fulltime employees and 300 volunteers across 45 counties, with a budget of $6 million, down from $9.5 million prior to the COVID epoch. She says she expects the budget to return to the higher figure in the next 18 months: “We were forced to learn some new efficiencies”—in management-by-computer and granting wishes remotely—“and now I think it’s going to remain part of our way of doing business.”

Her use of the word “business” is no Forbes-ian slip. Her late father was a financial adviser and her mom, who currently lives with the family in Stolo’s Roseville home, is a retired pediatric oncology nurse who worked at the highly respected Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital in Palo Alto. “I’m definitely a combination of them,” Stolo says. “To run a successful nonprofit, you’d better run it like a business if you really want to help people. Competency and caring have to work together.”

Stolo’s husband, Keith E. Diederich, is the CEO of The Gathering Inn, a double-entendre name you’ve got to love when you realize its mission is to provide 24/7 shelters and services for the homeless at four different Placer County venues.

The couple met at a conference for nonprofit managers. Diederich came to the marriage with four children. Together, he and Stolo added two more. The net result is that at the moment, they have six children between them, three of them teenagers living at home. All of the kids are eager, frequent and freeway-close volunteers for both parents, Stolo says proudly.

The pandemic has required Make-A-Wish to scale down the granting of some of the wishes it receives, Stolo says. For example, gone are the days (for now) when the foundation was able to grant its most exotic wish to date to eight-year-old leukemia patient Grayson, ”a little boy who wanted to go see the glow-worm caves in New Zealand.” Summoning up resources from the worldwide network of other Make-A-Wish foundation branches, Stolo’s group was able to make all the international connections, get the flights, hotel accommodations and, most important of all, Grayson into those caves.

Then there was Ethan, a cystic fibrosis patient. At six years old, “He wanted to be a garbage man more than anything!” says Stolo, her low, expressive voice almost slipping into the alto of a little boy. The garbage-truck driver at Waste Management, who took Ethan on his collection route from Rancho Cordova through Sacramento—with stops along the way so schoolkids and neighbors could root for the team—told Stolo it had been “the first time in all his years as a driver he had to install a booster seat in the truck’s cab.”

Stolo offers two lovely post scripts to these anecdotes.

First, both of these kids are still with us more than five years later. Stolo had told me in an interview a few years ago that a pernicious myth surrounding Make-A-Wish is that what the group does is “arrange for dying children to go to Disneyland.” In fact, while all of the kids and teens served by the group are ill, “Seventy-five percent go on to lead long, productive lives,” she says.

Second: that garbage-truck driver still has dinner regularly with Ethan. Okay, I’ll race you to the Kleenex box.

“I’ve also learned to slow down a little,” she says.

Seeing one of my eyebrows go up high enough to trip low-flying wrens, she laughs. “No, no, really I have. I’m not like I was when you first interviewed me.” To which I mean to reply, but don’t, “You wish.”

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).