Surly Words and Whirlybirds: An Aviation Memory

If God had wanted man to fly he’d have given him travel points

By Ed Goldman

I once asked my dad’s friend Maury Freed, an aeronautical engineer (yes, an actual rocket scientist) about in-flight turbulence, the phenomenon that inspires even the steeliest of experienced travelers to develop a fear of flying.

He explained that a jet plane flies in “a lane” and that just as you may encounter a bumpy road on terra firma, sometimes a sky lane can be bumpy. “But in 95 percent of the cases,” he said, “if the plane stays in its lane, even if the ride’s bumpy, you won’t go off the road, so to speak.”

Rotor rooter

Maury was a pipe-smoking, warmhearted, bespectacled man with dark black hair, dark eyebrows and thin mustache. We had been talking aviation because at the time (1974) I was about to begin going on weekly helicopter flights for the city of Lakewood, California. The purpose was for me to shoot aerial photographs that would document the progress of a large redevelopment project in a recently annexed potion of the city. After Maury reassured me about airplane turbulence, I asked him what he thought of helicopters, hoping for a similarly upbeat treatise on their safety. But he took the pipe out of his mouth and said with absolute earnest, “Aerodynamically, there’s no damn reason they should be able to fly. They scare the hell out of me.”

At this point, all of Maury’s physical attributes—the black hair, eyebrows and, eyeglasses—rearranged themselves until he was a dead ringer for Groucho Marx-as-Satan. The pipe became a cigar, the mustache composed of greasepaint.

“A helicopter has no glide ratio if it gets in trouble, like a plane does,” he went on as I tried to imagine that members of the Norman Luboff Choir were in my head singing “The Yellow Rose of Texas” at the top of their lungs, straining to out-shout each other while simultaneously Irish clog-dancing as noisily as possible.

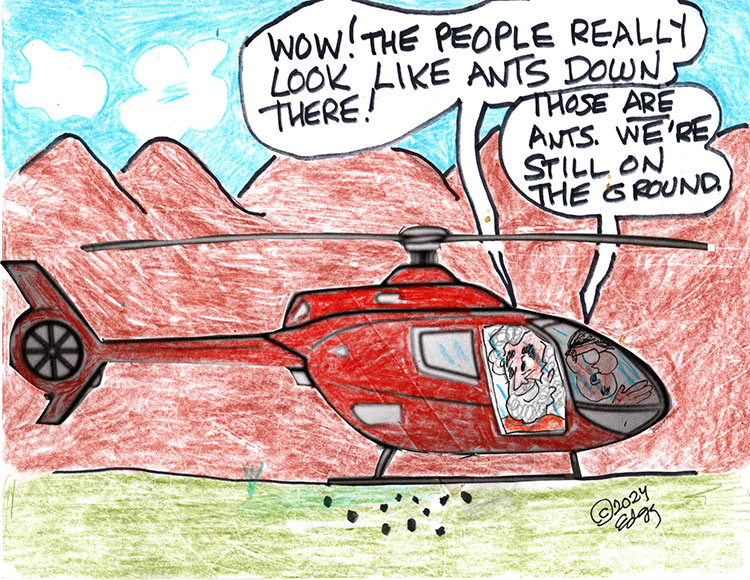

As it happened, I loved flying in the chopper, a Hughes 300CQ (the “q” stood for “quiet”) designed specifically for law enforcement. It could have been as easily deployed to do those traffic reports everyone hates listening to when they’re already stuck in the mire—as in hearing, “Hey, things are bottling up on the 405. Better head over to the Harbor Freeway!” when you’ve just pulled onto the 405.

I flew every Friday afternoon with a pilot named Don who’d been expert enough to train helicopter pilots for duty in Vietnam so I felt pretty sure that he knew what he was doing. In fact, he got me so confident that within two weeks I started flying with the door off on my side and even dangling my legs out, the better to shoot near-panoramic pictures of the redevelopment area without any window-glass reflection.

It became so addictive I thought of asking Don if he could train me to fly a chopper. What I loved about it was that unlike in a plane, glide ratio or not, when you wanted to make a left turn you could come to a complete midair stop and turn left. That felt like the sort of thing Superman could do.

But then, two things happened. First, I was hired by the city of Sacramento to become its public information tzar and would be leaving Southern California in a matter of weeks. Second—and this is much more significant—on my final flight with Don, the LA County Sheriff’s Department radioed him to pursue a robbery suspect tearing through the streets of Lakewood, its next-door neighbor Bellflower and the nearby city of Paramount.

I found out in a hurry how gingerly Don had been treating me on our weekly flights. We were suddenly flying 95 miles per hour and Don was tilting the helicopter left and right to make sweeping diagonal passes over the suspect’s pickup truck, which Don had spotted about 25 seconds after the call came in. Department personnel provided the ever-changing coordinates of the perp’s escape trajectory.

In a few minutes, Don got his helicopter positioned about five stories up from the pickup truck and just coasted along with him down the city streets. The police units on the ground had merely to keep the chopper in sight to apprehend the bad guy. As I watched that happen—they set up a roadblock and made the arrest in what seemed a matter of moments—I had a fleeting thought that the wrongdoer might have had a movie-gangster complex and begin firing his gun into the air, injuring or killing me—or, worse yet, wounding Don enough for him to say, “Ed, you gotta land this for us.”

Later that night, after a calming hot bath and eight or nine drinks, I reflected that anyone who thinks that a police helicopter won’t be able to track his getaway car deserves the justice about to be meted out to him. While they’re at it, they might also toss in some brains. And if they really want to be cruel, they could have Maury Freed visit him in jail to explain how futile his fleeing had been.

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).