Judge William Shubb on Law, Longevity and Even Ukuleles

The Eastern District justice presides over a delightful lunch

By Ed Goldman

While his job title would allow William Shubb to occasionally be, well, judgmental—after all, he’s a judge—what he seems to be most is contemplative, kind and pretty funny.

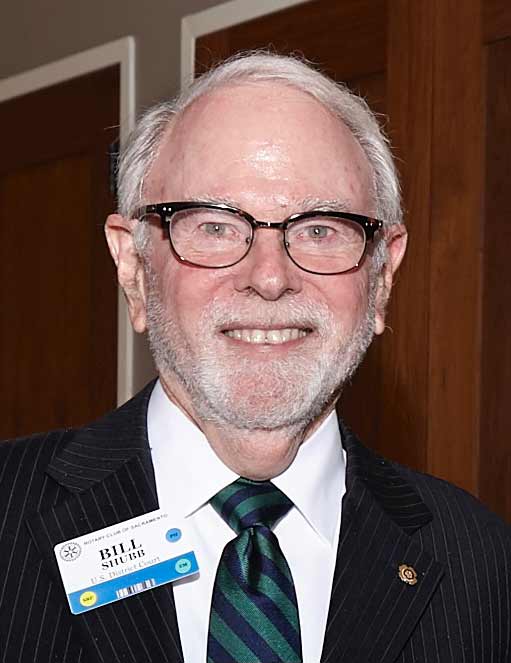

At my invitation, Shubb, senior judge of the U.S. District Court (for California’s eastern district), has joined me at The Sutter Club, the downtown Sacramento landmark. Shubb could be one as well— but that would require him to stand still. And at 84—with a lively gait, clear never-miss-a-thing eyes, a robe-full of anecdotes and an exit strategy that he summarizes as “dying at my desk someday”—he’s a deeply experienced barrister but to me, a youthful lunch companion.

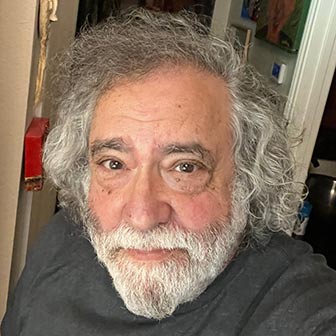

Sandra and Judge William Shubb

“I went into the law because my dad said since I was always arguing with him, I ought to be a lawyer,” Shubb says over a semi-Spartan lunch of a half sandwich, cottage cheese and iced tea (“My wife likes to make big dinners so it wouldn’t do for me to get full at lunchtime,” he explains).

Shubb’s dad, Ben, had a career in newspapers—not as a reporter or editor but as the guy who made sure everyone received the daily paper: first, the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, later the San Francisco Examiner. He began as a copy boy, then drove the delivery truck and, in his later years, dispatched the trucks. “He retired three times,” Shubb says with a positively impish grin.

Fascinated from an early age with lawyering “based entirely on watching TV shows and seeing movies that featured attorneys in them,” he was one of a group of students in high school who, as part of a Rotary-sponsored Career Day, got to spend time in the office of a prominent lawyer.

“At one point, I asked him, ‘How often do you go to trial?’ and he laughed and said, ‘Never. What you want to talk to is a trial attorney.'” Shubb shrugs. “He was in an entirely different branch of the law. But I already felt that litigation would be the only one for me.”

Born in the Piedmont section of Oakland to Ben and Bernice Shubb, the judge-in-waiting studied journalism at UC Berkeley and, like his dad before him, worked as a copy boy to support himself (for the SF Examiner—part-time during the school year, fulltime in the summer). He was accepted into the university’s Boalt School of Law, where he excelled academically—and also, though he didn’t know it at the time, professionally.

While he says he had no idea what a law clerk was or did, he became one, from 1963-1965 for Judge Sherrill Halbert of the U.S. District Court, the same post Shubb now has. Shubb beat out other top-of-their-class nominees “because the other guys wanted to do Law Review—yet I’d been told that clerking for a federal judge would not only provide a great learning experience but would also always be a highlight of my résumé.”

Halbert, Shubb recalls, “was what you’d call a judicial conservative, meaning he believed in and strictly adhered to the United States Constitution. I learned more in that year than I’d have ever learned writing for Law Review because I learned it from the inside, from what went into a judge’s thinking.” In fact, when Shubb went into private practice, he was surprised to find that because of his experience, he “sometimes knew more than even some senior partners” in his law firm knew “about how a case might be viewed by a judge.”

From 1974 to 1980, Shubb was an associate attorney of the law firm Diepenbrock, Wulff, Plant & Hannegan, which he returned to in 1981 as a partner, after serving from 1980-1981 as the United States Attorney for the district. In 1990, then-President George H.W. Bush nominated him to his current seat. (In the intervening years he had served as Assistant U.S. Attorney of the Eastern District from 1965-1971, then as Chief Assistant U.S. Attorney of same.)

Judge Shubb

Among his more media-glare worthy cases was his deciding last September on the sentencing of Sherri Papini, the young woman who’d faked her own abduction in 2016 and, when “found” a few weeks later, on Thanksgiving Day, at first lied to the FBI about the whole sorry mess. Shubb sentenced her to 18 months in prison. Predictably, he didn’t comment on his ruling to me—exhibiting a rare moment of propriety, I didn’t ask him to—and in fact he wasn’t even mentioned in much of the press coverage.

“I sometimes find out more about the background of certain cases when I read a well-researched newspaper story about it,” he says. “Reporters can go into things that ultimately have little or nothing to do with what I’m going to base my decisions on: the evidence presented by the lawyers on both sides.” This is not to suggest that Shubb thinks reporters are always accurate. Or “ever completely accurate.” I decide to waive my right to cross-examine. We’re having too nice a time—and besides, I think he’s right.

Shubb taught one class a semester for a few years both at McGeorge School of Law and UC Davis’s but says he didn’t really enjoy the experiences. “It was a lot of work—and I think some students were scared away from taking my classes when they referred to as Judge William Shubb instead of Professor William Shubb in the catalogue.” I ask if he’d consider writing a book about his experiences as a lawyer and judge and he shakes his head.

“I’m at my best in the courtroom and one-on-one with somebody,” he says. He says his time as a law clerk taught him the value of mentoring (he’s had 64 law clerks)—and on December 22, he’ll administer the oath of office to new Superior Court Judge Steve Lau, who was one of them. “It’s pretty special,” he says.

Judge Shubb and his wife Sandra have three grown daughters— Alisa, Carissa and Victoria—and four grandchildren (“two boys and two girls,” his honor proudly informs me).

One of the more enjoyable aspects of chatting with Judge Shubb was discovering not only that he liked to play the ukulele to relax but also that his younger brother, Rick, invented the Shubb capo, the device that slips over a guitar’s neck to help players change keys by shortening the length of the strings.

“When I decided I wanted to buy a uke, I took Rick with me since he knew everything about instruments I didn’t,” he says, smiling. “When I asked about tuning it, or maybe changing keys, the guy who owned the music store said I could use the same kind of capo on a uke that’s used on a banjo. Rick said that wasn’t true. The guy said something like, ‘Listen, I’ve sold a lot of capos’ and Rick just smiled and said, ‘No, I’ve sold a lot of capos’ and revealed who he was.”

The store owner’s ignorance (and arrogance) resulted in Rick Shubb’s going off and creating a capo specifically for ukuleles. “That guy should have listened to my brother,” Shubb says summarily—but not in the least judgmentally.

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).

Yes, Virginia

A Weekly Blog by Virginia Varela

President, Golden Pacific Bank, a Division of SoFi Bank, Inc.

photo by Phoebe Verkouw

BEING A MENTOR PROVIDES TEACHING (AND LEARNING) MOMENTS

If you consider yourself a leader in your field, you should be able to name at least one person whom you’re committed to mentoring. If you can’t, I suggest you fix it.

Get out of yourself and share your skills!

Mentoring is a must for leadership because it brings out not only the best in other people but also in you. Mentoring builds leadership at all levels of an organization or community.

There is a satisfaction that comes from giving back. You can gain a new perspective—and a renewed confidence in yourself and your skills as you shape the leaders of tomorrow and learn from them.

I definitely find mentoring to be a two-way street. As a mentor, you are in a great position to step back and see the bigger picture of your mentees’ professional lives from their perspective. They absolutely provide a learning moment.

You simply have to drop the perceived pecking order, keep open, and be willing to let your mentoring session work both ways.

Last weekend I met a fine young man named Jesus. At 21, he is bright, entrepreneurial, willing to learn and grow. In short, an impressive sort that I am confident will be a force to contend with, no matter his future endeavors.

Virginia with Jesus at Barrio cafe and coffee shop in Sacramento’s South Land Park.

While he was interested in learning from me, I found myself curious and mesmerized by his youthful perspective. He challenged me, saying that people his age are suffering with worry about the environment, guns and violence, and a lack of a functioning government.

I saw things and issues from a new light: How would I feel if many of my limited adult years were framed by COVID, burgeoning environmental disasters, and economic insecurities? How would I behave, and what would motivate me in this confusing landscape?

In short, the teacher benefited as much from the lessons as the student.

sponsored content