For My Daughter, on the Eve of Her 35th Birthday

With a word or two about the miracle drug called Infants’ Tylenol

By Ed Goldman

My daughter—writer-director-singer-actress-publisher Jessica Laskey—turns 35 tomorrow. This happens to be the same age her mom and I were when she was born on Easter Sunday in 1986, completely upsetting our brunch plans.

The age comparison is one of those factoids that can seem either plump with meaning or can serve as usable fodder for the family numerologist. In fact, it’s not very unusual. If you’re fortunate enough to stick around and watch your children grow, the overlapping age thing will always be waiting in the wings, and rarely relevant: “Well, you’re eight now! I, too, was once eight!”

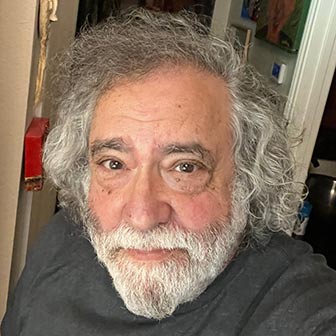

In the gene pool.

I tried to amuse a friend’s son a couple of years ago when the boy told me his age and I said I’d been that age five times already. It went something like this:

FRIEND’S SON: I’m 12, Uncle Ed.

ME: How about that! You know, I’ve been 12 five times!

FRIEND’S SON: ??

ME: Five times 12 is 60.

FRIEND’S SON: My mom says you’re like, 68.

ME: Well, yes, but—

FRIEND’S SON: So you’ve been 12 almost six times, not just five. In four years, you’ll be 72. That’s six times 12.

ME: Technically, that’s true. But—

FRIEND’S SON: And my mom says you’re not really my uncle.

ME: Also technically true. So maybe you should give me back the new video game I gave you.

FRIEND’S SON: Ha-ha-ha. You don’t even know the name of—

ME: It’s the Ratchet & Clank Rift Apart Launch Edition. I’ll wait while you go to your room to get it.

FRIEND’S SON: (Beginning to wipe non-existent tears from his eyes) But… but…you’re my favorite uncle in the whole galaxy, Uncle Ed!

—My dad was 34 when I was born, and my mom had just turned 33 two weeks earlier. They wouldn’t have cared about the connection between their ages and my age when I turned 33 and 34 (well, my dad wouldn’t have, anyway, having died when I was 25). But I was 55 when my mom died at 88; still, I don’t recall our ever having discussed how she felt when I chalked up the birthdays she’d already had. It could have been one of the very few things in this world about which she didn’t have a comment. As she used to say, “Everyone’s entitled to my own opinion.”

In retrospect, I think if she’d been reticent on this subject it would have surprised me—because even though she wasn’t into numerology, she enjoyed reading “Omarr Reads the Stars” in the L.A. Times every day, an enormously popular syndicated column (called “Sun Sign Horoscope” in some markets). Omarr’s first name was Sydney, which, for me, was just incongruous enough to take some of the exotica out of him. It would have been like finding out the world’s greatest surfer was named Kahuna Malakahini Noodlebaum.

To be sure, there was a major difference between my parents bringing me into the world in their still-early 30s and my daughter being born when her mom Jane and I were 35: I was my folks’ fourth child; Jessica was our one-and-only one.

My parents had grown relaxed in their roles by the time I came along, owing to experience. We thought we were the same, owing to absolutely nothing. I thought perhaps Jane’s and my separate, then combined, life experience had rendered us fairly existential: our lives, then life, had been thoroughly unplanned. I thought it would have given us a much calmer demeanor the first time our daughter ran a fever of 107 degrees.

I remember our grabbing her (she was not quite a year old) and speeding to a 24-hour pediatric clinic, being mindful, before that word went all quasi-mystical on us, to observe all traffic laws and drunken pedestrians stumbling out of neighborhood watering holes with names like My Mistress Doesn’t Understand Me and Chez It Isn’t So.

“Your daughter’s fever doesn’t really concern me,” the young doctor at the clinic said. We resisted screaming, “Well, it sure as hell concerns US!” because, to reiterate, we were trying to be composed and existential. The physician, a woman about our age, saw the incredulity in our perhaps non-serene looks—looks that Spielberg could have used as models for the melting Nazi faces if he were ever to remake “Raiders of the Lost Ark” (it had come out a few years earlier).

“Children this age run ridiculously high fevers,” the doctor said. “I’ve tested her reflexes, and she doesn’t seem to be in any discomfort. Take her home, give her a slightly cool bath and Infants’ Tylenol. She’ll be fine in a few hours.”

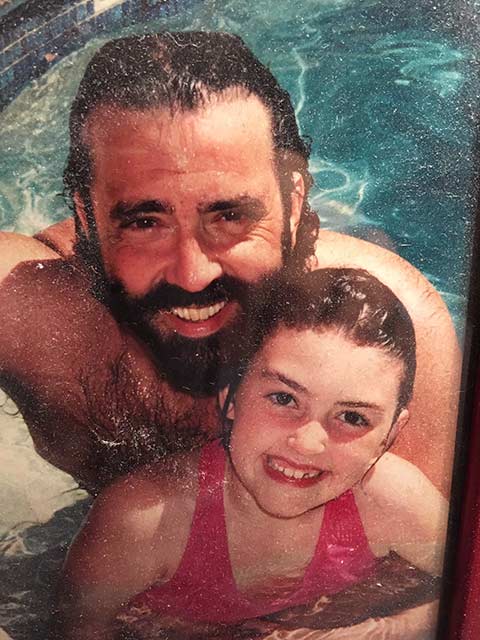

We did as told. But because Jessica was used to one of us climbing into the bathtub with her, I was elected. Holding her in the tepid water, I imagined I saw the fever drain from her little body, the way old-fashioned elevators looked as they descended behind their glass doors. After a few minutes, I handed her to Jane, who dried her and administered the Infants’ Tylenol (note to the squeamish: it isn’t given orally to children that young).

Within 10 minutes, Jessica’s fever was gone and she was fast asleep. Her mother, relieved beyond belief, also conked out. This left me, fully refreshed from a bath in the wee hours, wide awake. In fact, pretty damned peppy.

Fortunately, I was a night owl, so I went into my office—where I was to be found, sound asleep, at noon. Jane later told me that with my face on the desk and my arm outstretched, I looked like a guy “reaching for his pen to write a suicide note” after the arsenic caplets had reached his system.

I was angry with my lack of vigor, and began to wonder if I had begun slowing down a bit. After all, I was now 36 years old—a full year older than what my daughter turns tomorrow. I wish her love and a preposterously long life.

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).