Sylvia Fitzgerald Appraises Art, Antiques and Barns

Some timely insights about timeless treasures

By Ed Goldman

Oscar Wilde once said, “A cynic is a man who knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing.” True enough—but what if that person weren’t a man, weren’t a cynic and actually knew both the price and the value of something? She might be Sylvia Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald, who appraises art and antiques for individuals as well to determine the worth of an estate’s contents, says that when she does an appraisal she first wants to understand why she’s being hired to do so. “I want to know if someone is simply trying to insure a piece, is hoping to sell it to an auction house or a secondary market or wants to turn it to salvage,” she says.

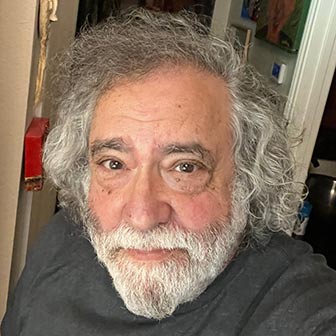

Sylvia Fitzgerald, by Jesse Bravo

At a recent lunch in The Sutter Club, the private downtown Sacramento landmark where she’s a third-generation member (she’s also a fifth-generation Sacramentan), Fitzgerald admits she’s candid “possibly to a fault. I won’t let a client be taken advantage of and I’ll tell them right off the bat if the thing they think has tremendous retail value actually does—or doesn’t. One of my mottoes is, ‘Never let your alligator mouth overcome your hummingbird ass.'”

It is, to me, an expression that’s simultaneously colorful, possibly inexplicable and the sort of thing you’d hear someone say on a loading dock or in a gangster movie. But her other personal mantra is, “Do right./Sleep at night.” That one I get immediately.

For 25 years, Fitzgerald, whom you can learn more about at her website, www.sylfitz.com, has been an accredited member of the International Society of Appraisers and has been a private collector for 10 years longer than that. She doesn’t pretend to know everything about everything, and says she frequently relies on a worldwide network of peers, colleagues and friends when a piece or project stumps her. “I always offer to pay” for her pals’ help, she says, “especially on an IC basis. That stands for introductory commission, meaning, ‘If you hadn’t referred this client to me, I might never have met this client.’ But a lot of my folks decline my offer—and I always return the favor when they call on me. It’s true professional courtesy.”

I met Fitzgerald several weeks before this interview when she was curating a show-and-tell art dinner for The Sutter Club, at which collector-members displayed one or two of their acquisitions for an evening. She selected two of my paintings, by Roland Petersen and the late Gary Pruner, for the event. Since then she’s been brokering a few other pieces I’ve bought over my 40+ years as a collector, principally of contemporary Northern California art that comprised the so-called Funk Movement of the 1970s-90s.

I mention this because in that time I’ve semi-liquidated my collection three or four times—and found Fitzgerald the most cooperative, honest, turn-key broker of them all. How turnkey, you ask? She lifted, crated and wrapped everything I was hoping to unload. She’s a former gymnast and while she did bring along a colleague of hers to help, at 61 years old she was doing work that’s physically demanding. And she wouldn’t let her client (at least, this client) lift a finger to help her.

How honest, you further ask? When she came to my place to look at my artwork, she told me flat-out that things I thought might fetch a respectable price at auction or from a private collector simply wouldn’t—or more to the point, simply wouldn’t right away. “Art has its seasons,” she said at the time. “Things are suddenly in, then suddenly not. You just have to watch the market and be patient.”

Fitzgerald enjoys recounting that she began her appraiser career “with $5,000 in a spare room in my house.” She financed her enterprise when her mom held a garage sale in which “some of my aunt’s bottles didn’t sell for even 25 cents. I caught them mid-flight to the trash.” They turned out to be made by Lalique—which I’m sure you know, is the posh line of crystal champagne flutes, shot glasses, tumblers and more (on its website it refers to its brand as “the ultimate symbol of French luxury”).

Fitzgerald starting haunting garage and estate sales, discovering riches their sellers viewed as rubbish. Her business, Art, Appraisals & Estate Services (A.A.E.S.) was launched.

When I ask her to call out the biggest mistake people make when selling or acquiring art or antiques, she offers a quicksilver grin, which telegraphs that what she has to say may not be all that comforting for people “who believe that a rolltop desk sitting in their garage came over on the Mayflower. Look, people, it didn’t, all right? It wouldn’t have even fit!”

“I think the biggest mistake people make is they have disconnected notions of something’s value based on unsubstantiated information,” Fitzgerald says. “They may tell me they saw a piece just like this on Antiques Road Show. I tell them my opinions are based on research.”

Finally, when I mention that I was surprised by how taxing her work could be, she says, “Yeah, it ain’t all that glamorous. The best stuff I ever find is in barns.” Ranchers and farmers, take note.

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).

Yes, Virginia

A Weekly Blog by Virginia Varela

President, Golden Pacific Bank, a Division of SoFi Bank, Inc.

photo by Phoebe Verkouw

MISUSING THE FDIC LOGO IS A NO-NO

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, more commonly known as “FDIC,” is a government agency that insures deposits at certain FDIC-insured banks and savings associations—up to $250,000 per depositor for each account ownership category.

Deposit insurance promotes confidence in the banking system and is one of the benefits of being a regulated FDIC bank. Deposit insurance was created following the historic Great Depression ghast began with the Wall Street crash of 1929 and continued on through the 1930s. Banks were failing and customers had no access to their funds.

At this time of marketplace changes, with new fintech firms and technological advancements, there is a blurring of lines between what is commonly understood as a bank versus some other type of financial organization.

Some non-bank entities have preyed on consumers by causing confusion and falsely using the FDIC name or logo in their advertising and marketing materials when they shouldn’t. Last week, regulators took action by issuing a new final rule on false advertising, misrepresentation of insured status, and misuse of the FDIC’s name or logo. In a regulatory statement, regulators noted:

- Misrepresenting the FDIC logo or name will typically be a material misrepresentation.

- Misrepresentation or misuse of the FDIC name or logo harms customers and puts them at significant risk of unexpected losses.

- Misuse of the FDIC name or logo harms honest companies.

Be sure to look for the FDIC logo when you do your banking. If it says “FDIC-insured” with an FDIC logo, be comforted that your funds are protected.

sponsored content