Norman Hile’s War Ended—Or Did It?

On the day before Veterans Day, we discuss a new book about one man’s Vietnam War epoch

By Ed Goldman

I’m not referring to Afghanistan, the latest example of America’s blundering into a country it didn’t understand, supposedly on behalf of people who never stepped up, and for a cause that was dubious at best—and which, over the course of 20+ years, cost thousands of lives and trillions of dollars.

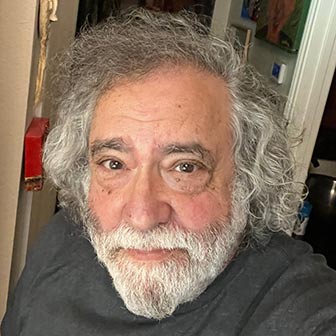

Norm Hile Then

Hile’s own pointless war is depicted in his book, “Keeping Each Other Alive—A Vietnam War Memoir” (available at www.iuniverse.com). It’s adapted from letters Hile sent to his family—he includes copies of the handwritten originals in the book’s appendix—when he served as a U.S. Army artillery forward and aerial observer in South Vietnam for 10 long months, starting in August 1970.

“I started dictating the book in the 1980s,” Hile tells me one recent morning at Pachamama, a coffee shop near the home he shares in East Sacramento with his wife, attorney Belinda Beckett, and two very doted-on dogs. The home is also a favorite venue for his grown daughters and four grandchildren, who range in age from “not quite two” to “not quite four” years old.

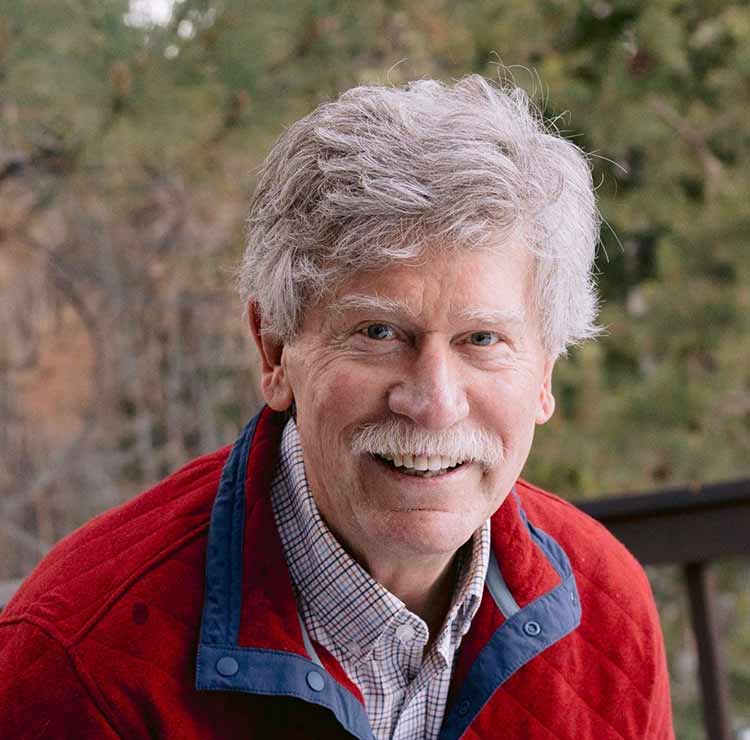

At 76, Hile is a senior counsel at the international law firm, Orrick, which has offices in California’s capital. He’s a soft-spoken, trim man with a tidy mustache and an enviable head of thick hair. But his affable manner barely conceals, as he warms to his subject, his lingering anger for, and perplexity at, the military “and its entire way of doing things.”

He says that writing the book—which I found to be candid, heartfelt but unsentimental—”had a cathartic effect. While working on the first part of the book, which had a lot about the actual fighting, I found myself dealing with some PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] issues. But as I continued along, and started reliving some of the less awful stuff, I started to enjoy the (writing) process.”

He wrote and published the book, Hile says, “for a couple of reasons. One, I wanted my family to know something about the things I never like talking about. But two, I wanted to show just how badly things worked in the military, and maybe even caution readers to never allow this kind of war to happen again.”

In the field, Hile was injured when he caught some shrapnel in his leg. “It was, as Monty Python says, ‘Just a flesh wound’ [I’ll explain that reference in a moment] and it didn’t even get me out of combat that day. We had some great medics, and one came to me immediately, removed the shrapnel and gave me a shot to prevent infection, then moved on.” About that tongue-in-cheek reference: As a knight is progressively dismembered in “Monty Python and The Holy Grail” this is one of the things he says, thinking it will torment his torturers.

Norm Hile Today

Hile received a Purple Heart for being injured, and thereby hangs a brief tale of vainglory: His captain recommended him for the honor, then recommended himself for not only a Purple Heart but also, down the line, a Silver Star, which is the U.S. Armed Forces’ third-highest combat award for valor. “I was quite surprised to find that people could nominate themselves for some of these awards,” Hile says. His grin borders on a grimace.

Because Hile is a lawyer, I half-expected reading his prose to be akin to trudging through molasses. The pleasant surprise about “Keeping Each Other Alive” is that it’s a pleasing read: Swift-paced, accessible and, as aforementioned, candid. At coffee I mention that its dispassionate immediacy reminds me a bit of Michael Herr’s “Dispatches,” the 1977 book in which the no-nonsense/no-gorgeous prose of the author, who was covering the war for Esquire magazine, not only garnered high praise and sales but also drew the attention of director Francis Ford Coppola, who was looking for someone to help him bring an organizing coherence (which became Martin Sheen’s narration) to his screenplay for “Apocalypse Now.” (It should be noted that Herr later admitted he’d invented a couple of key characters in “Dispatches.”)

“Actually,” Hile says, “my inspiration, or influence, was a book called ‘The Things They Carried’ by Tim O’Brien, which told what it was really like to be a grunt.” (Grunts are infantrymen. The term stands for General Replacement Unit, Not Trained.)

The most moving part of Hile’s book depicts what it was like, upon completing his military service, to come back to a country that maltreated or even joked about Vietnam veterans. “It also seemed as though every TV show featured a murderer who was a psychotic Vietnam veteran,” he recalls.

But toward the end of our chat, Hile tells me that several years later, he joined some of his fellow ex-soldiers in a Veterans Day parade through downtown Sacramento. “This time we were cheered,” he says. It was a bittersweet moment for him as he recounted that day.

I probably compound the ambiguity when, upon parting, I do something I rarely do but always should: I thank him for his service.

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).

Yes, Virginia

A Weekly Blog by Virginia Varela

President and CEO, Golden Pacific Bank

photo by Phoebe Verkouw

A POST OFFICE IS NOT A BANK

In the past few weeks, the U.S. Postal Service has quietly begun piloting banking services—such as check cashing, bill paying and ATM access— in Washington, DC; Falls Church, Virginia; Baltimore, Maryland; and the Bronx, New York.

This is one “pilot” that should be grounded before it takes off.

The USPS is the same organization that’s billions of dollars in debt and is considering slowing the delivery of mail across the nation because it can’t keep up. You may therefore be asking, “What can be slower than snail mail?” We may be about to find out.

The Postal Service needs to get its act together and deliver the mail, not get into financial services that it neither understands nor is equipped to provide.

To be sure, there is a genuine concern that many Americans are “under-banked.” According to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., about 8.4 million households in the US are totally “un-banked,” and 24.2 million more are “under-banked”—meaning they have limited or no access to bank accounts, or ready access to financial services such as check cashing, ATM access, bill paying, money orders and wire transfers.

But let’s consider a root cause of this.

The number of un-banked households increased dramatically as the number of community banks across the nation failed — even though community bankers play a critical role in providing credit, liquidity and investments to their communities.

The number of community banks in the US has been declining for the past two decades. In 1997 there were 10,700 banks in the US; in 2016 there were 5,600, and today there are fewer than 4,740 banks across the country.

Why did so many community banks close or agree to be acquired, and why are there so few new community banks opening up? I’ll tell you one big reason—the regulatory burden. Over the years, the government and regulators have created onerous requirements for banks, regardless of size or complexity. The government has set forth so many rules and requirements that it’s very difficult to run a small bank efficiently and make a buck.

Logic and a sound mind would suggest that the government and regulators address the problem of “under-banked” Americans by promoting a comeback in community banks by scaling back on the regulatory requirements for smaller, more traditional and less complex banks. Perhaps small community banks should be treated more like credit unions, which don’t pay federal taxes and have less stringent requirements on data collection for bank secrecy and fraud reporting.

Community banks understand their communities, they are set up and experienced in banking, and have a track record. Unlike the United States Postal Service.

Community banks were established in a democratic, capitalist nation to serve all types of folks. Over time, the government disrupted that purpose when it applied all kinds of rules to all banks, regardless of size, with many of the same burdensome requirements. Small banks can’t keep up with the rules. The answer to the concern of serving the un-banked, is to lighten the load for small community banks.

But opening up banks in a rapidly defunct post office makes zero sense.

Take this idea and RETURN TO SENDER.

sponsored content