Scott Shields Curates the New, the Old and the Once-New at the West’s Oldest Art Museum

An art historian from the “give-the-reader-a-break school” of writing

By Ed Goldman

When I ask him to summarize his workday for the past 21 years as associate director and chief curator of the Crocker Art Museum—the oldest art museum west of the Mississippi (and one of the most modern, as we’ll discover in a moment)—Scott Shields grins.

Candid but also somewhat shy when it comes to being interviewed about himself instead of the art and artists he devotes his days and nights to, he says, “Oh, gee, let’s see. Each day I spend a lot of time on the phone and send dozens of thank-you notes to donors, collectors and artists.”

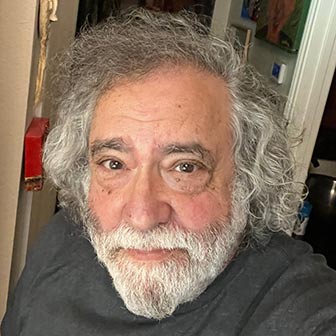

Dr. Scott Shields

Narrowing his eyes with mock-solemnity, he says, “But I have a feeling you’re looking for a more serious answer.” He grins again.

He’s actually a very serious guy. Dr. Shields—at a very youthful 53, he has a Ph.D. in art history from the University of Kansas, Lawrence—has curated some of the most significant exhibitions at the Crocker throughout the past two decades, including the recent retrospective of Wayne Thiebaud’s paintings on the occasion of the artist’s 100-year birthday. It was perhaps the only centennial celebration of an artist to which the artist not only showed up but did so with impressive vitality.

In addition to Thiebaud, painters Roland Petersen, and the late Richard Diebenkorn, Joan Brown, Mel Ramos, and Elmer Bischoff are among the contemporary artists whose work is shown at the Crocker. But as Shields and his boss Lial Jones—who’s the Mort and Marcy Friedman director and chief executive officer of the museum— like to point out, much of its collection has always been contemporary for the time in which the art was created.

So, you’ll find the work of one of California’s (and Sacramento’s) earliest painters of note, Amanda Austin (1859–1917) here, as well as that of California landscape master Norton Bush (1834-1894).

Shields dreamt up, curated or co-curated, and has nearly always made happen dozens of shows for the Crocker.

What may not be commonly known about a curator’s job is that, yes, he or she not only finds the art to be shown—from traveling exhibits, individual donors and continuous research—but that he or she also writes the narratives about the presentation, sometimes in a booklet format, sometimes for a lengthier online discussion. “As a writer in a very esoteric field,” he says, “I belong to the give-the-reader-a-break school. I spell out the history and the artist’s philosophy about a particular piece; but ultimately, it’s really what the world brings to appreciating art that matters.”

With a staff of about 17 direct- and non-direct-report employees—not to mention the calls he fields from artists, educators, members of the Crocker Art Museum Association’s board of directors, reporters and potential show sponsors—Shields’s writing hours would seem to fall prey to constant interruptions. “That’s true,” he says, letting loose another of his frequent and charming grins, “and why I do so much of it not here. That’s why I have a home.”

He says that his natural skepticism is an aid when he puts on his art historian’s cap and finds in his research a slew of contradictions. These may range from simple booboos, like the birth- and death-dates of an artist but may also include writeups that “upon deeper inspection and painful headaches, turn out to be closer to fiction than documentation.

“What I’ve learned over and over as an art historian,” he adds, “is to trust absolutely no one—and to do the homework.”

After this interview, Shields contacted me to make sure “I adequately conveyed … my true passion at the Crocker, (which is) … building the collection. I get a lot of joy from working with donors and supporters to acquire new things for the museum and, fortunately, I’ve had a lot of wonderful people across all collecting areas to work with.”

Because Shields is surrounded by art every day—the museum is home to at least 15,000 paintings, drawings and sculptures—I wonder aloud if he’d ever been tempted to become an artist himself. His response reveals something of his modesty, candor and realistic view of himself and the world.

He says that when he was finishing his master’s degree in art history at the University of Kansas, where he returned to earn his doctoral degree, he was torn between settling into the academic life—his writing was already attracting positive attention in the right circles—or pursuing a career as a painter. A beloved mentor suggested he stick with education.

“To this day,” Shields says, “I wonder if he thought I was really that good as an art historian or really that bad as an artist.” Need I tell you that after he says this, he grins again?

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).