Miriam Revesz: New Filmmaker Debuts with a Five-Minute Masterwork

A study in mental health to commemorate the ADA’s 30th anniversary

By Ed Goldman

It’s tempting to write about my encountering two fawns the other afternoon when I go to chat with Miriam Revesz, who just completed her first film, “Voices from the Invisible.”

Fawn Number One stands in the middle of the long driveway that leads to the Revesz family home, a pebble’s skim from the American River (if you have a very good arm). The deer seems as curious about me as I am about it. But it quickly tires of me and scampers off to more pressing matters.

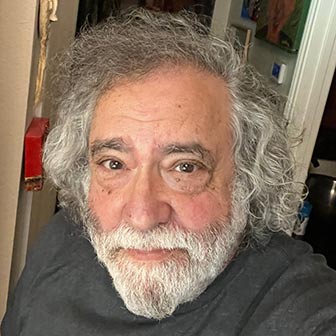

Miriam Revesz

The second fawn—at least at first glance—is Revesz herself, a porcelain-complexioned 30-year-old artist who’s spent at least half of her life being diagnosed, labeled, misdiagnosed and mislabeled by a parade of physicians, psychologists, mental health counselors and her own peers.

Revesz’s debut film just won a finalist award in the Awareness Campaign category of the seventh annual 2020 Easter Seals Disability Film Challenge. This year’s competition, which drew 87 entries, commemorated the three-decade anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The film is unnerving. It’s also hopeful, unsentimental and sometimes even funny, all in about five minutes. Revesz co-wrote, directed, narrates and stars in it. It’s about her battle with mental health. You can watch it on YouTube.

Over the past 15 years, Revesz says in her narration, she’s received numerous and sometimes contradictory evaluations. Nonetheless, “Here’s the truth,” she says in a steady, low voice. “I have severe OCD, treatment-resistant depression and anxiety, autism spectrum disorder, ADHD and PTSD. And I have a stack of medical records to prove it.” In the film, you see the actual stack as the conditions from which she suffers are highlighted in yellow.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with the acronyms above—which I hope means they haven’t touched your life or that of someone you love, though in the complexity of our day and age, I think that may be wishful hoping—they stand for obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Having only one can be life altering; bearing the full menu of maladies can be crippling on many levels.

Which is why I’m surprised, on meeting and chatting with Revesz, that she’s not exactly a faun. While some of the conditions occasionally “present” themselves, as medical terminology has it—a tendency to ask me to repeat certain questions, more for her intense clarification rather than anything resembling miscomprehension—she speaks with determination about wanting her film to help address the need for mental health funding “for research, not for the salaries of the presidents of mental health nonprofits,” she explains.

Revesz, who’s also a talented sculptor and painter, thinks she’s found her true calling as a moviemaker, though she’d like her next film to be feature-length and based-on-a-true-story fictional. I ask if she’d like to portray a character based on herself in that film and she says yes almost before I finish the question.

I think she’d do well. She has compelling, miss-nothing blue eyes, the aforementioned modulated voice and, without the wig she wears and toys with during our interview, a charismatic, Jean Seberg-like presence.

Would she also want to direct the film she’d write? ”Oh, no,” she says, with a throaty, relaxed laugh. “I’m done with that! I’d want a professional director to show me what I can do to improve. It’d be enough for me to just act in a film.”

Revesz is a lifelong learner. “My OCD makes me a great researcher,” she says with a broad smile. On screen, she warmly acknowledges the support she’s received from her family not only in creating the film but in helping her get to the point where she could let her creative juices flow into the project, which had rigid running-time and deadline restrictions.

Tom, Revesz’s father, is a retired family-practice physician; her mom, Eva, is a retired social worker. Revesz’s sister, Jessica, is a successful jewelry designer in Southern California. Her aunt, Talia Sarah Berger, and her mom receive screen credits.

One of the startling aspects of “Voices from the Invisible” is the inclusion of video footage from years ago showing Revesz breaking down in front of the camera. In the newer material, she plays herself, and, again in voiceover, tells us more about her still-in-progress journey.

“I have a real circus in my brain,” she remarks at one point. She itemizes some of the techniques she hoped would help her harness the runaways in her mind: “I tried meditation, aromatherapy, yoga, exercise, hypnosis, colonics, tinctures, cupping and the list goes on.” (Tinctures are plant or animal extracts, while cupping is an Asian therapy in which suction cups are placed on a patient’s skin, purportedly to assist blood flow.)

She says she’s collaborating with an award-winning ghostwriter to help her craft a book about her life and, now that she’s had a taste of it, wants to concentrate on filmmaking. Like many artists, she appreciates compliments about her work but also confides, “If I’d had more time, I’d have done so much differently.”

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).