Some Father’s Day Ruminations for People Who Are (or Have Had) Dads

Relaxing into responsibility at the age of 35

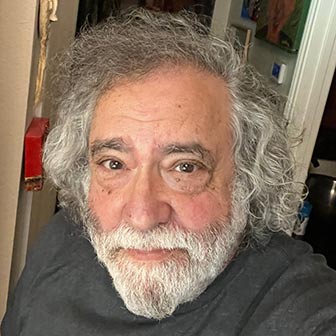

By Ed Goldman

“On Fodder’s Day, be sure to t’ank yer Mudder — ‘cause if it wuzn’t fer yer Mudder, yer Fodder wouldn’t be no Fodder.”

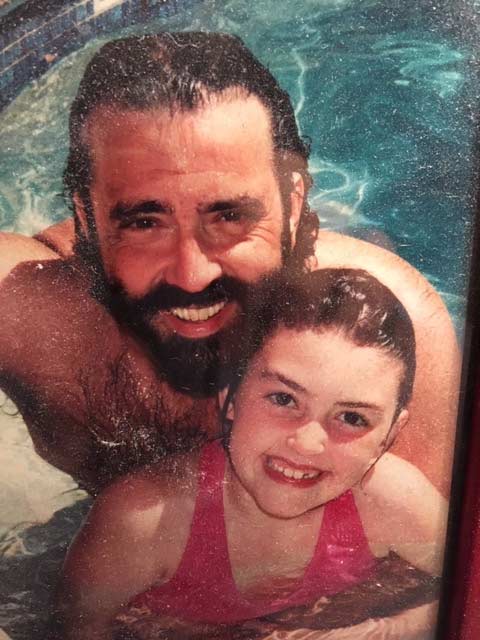

That always made sense to me, though what I really think about each Father’s Day is that if it wasn’t for my daughter, I’d have never been a father. I’m sure that seems painfully obvious but the fact remains that my entire way of barreling through life changed when my daughter Jessica was born 34 years ago on March 30.

If you’ve been lucky enough to be a father, to know your father or to know someone you’ve always suspected of being your father—I’m not trying to make trouble here, but DNA tests are more reliable than ever—you know that dadhood can be a pretty fraught walk in the park. Many dads go from being idolized (and idealized) when the kids are young; then we apparently go very stupid for a few years. If we’re lucky, things eventually even out a bit.

As Mark Twain famously summarized this irritating phenomenon, “When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.”

We still live in an era that allows children to blame their parents for everything—everything from the standard “Nobody ever bought me a shiny new bicycle” to “My parents never told me it gets dark when the sun goes down.”

Dad and Daughter, circa 1990. Photo by Jane Goldman.

To be fair, kids do give their parents credit for things, but mostly their genes: “I think I get my height from my mom. She was 6’11 in seventh grade, too.”

I’ve heard people in their 60s, 70s and even 80s talk endlessly about their low self-esteem because their mothers occasionally took a breath while praising them. Or their parents caused them to suffer “abandonment issues” by dying, even if they refrained from doing so until reaching an advanced age.

My older brothers and I used to believe we had three separate sets of parents even though the photos of our childhood reveal otherwise—the same two people, even though they visibly change as the chronology goes from my eldest brother, who’s nearly 10 years my senior, to me.

But you can understand the thinking of that assessment: as each kid came along, our folks had grown just a little more mature (if we were lucky) and maybe a little more relaxed (if we were very lucky). I was allowed to do things my brothers were barred from doing because by the time I was asking to do them, my mom and dad had figured out the requests weren’t all that outrageous.

Since my late wife Jane and I didn’t become parents until we were 35 years old, whatever maturity that might have accrued had Jessica been our second or third child, simply didn’t. But as 35-year-olds who’d enjoyed eight years of deliberate childlessness—but also a good deal of travel, a social life, home buying and, ultimately, a longing for responsibility—we were wised up, if not fully wise or wizened, by the time she popped out. And we were pretty relaxed as parents.

My daughter was born on Easter Sunday, 1986, and her birthday came out on that day again when she turned 11. It will again in 2059 and 2070, when she’ll be 73 and 84.

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).