Weather or Not

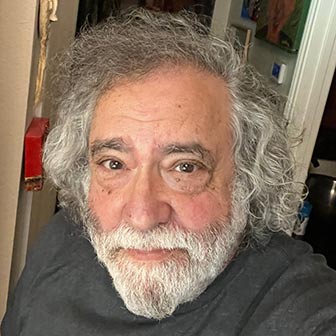

By Ed Goldman

You and I have something in common with most TV weather-casters, even if some of the latter are certified meteorologists: None of us really knows what the weather will be tomorrow.

We (and they) can hazard guesses, in their cases far more educated than mine—though for about 25 years, I would feel ”achy,” which later developed into arthritis, thanks so much, whenever the weather was going to change dramatically the next day (e.g., from sunny to rainy or vice versa).

Back when this first started to seem real, and something I wasn’t going to “grow out of” like thumb warts or thinking I still might become an international crime lord someday, my wife Jane suggested lending me out to the NBC-TV affiliate she reported and anchored for in Sacramento. “They could give the weather report then turn to you and say, ‘Here, with an opposing opinion of tomorrow’s forecast, as well as thumb warts he never outgrew…’”

As you know, predicting the weather has been a problem for, oh, ever—even before Mark Twain is believed to have said, “Everybody talks about the weather but nobody does anything about it.” This timeless quip was actually written by Charles Dudley Warner, who collaborated with Twain on “the Gilded Age,” according to my history consultant, Al Dunne— and backed up by his faithful, if perpetually disgruntled assistant, Ivana Reyes.

With climate change, which has also been around for, oh, ever, things have become especially difficult for TV weatherpersons. It doesn’t seem fair to hold them responsible for sudden changes in conditions that used to be pretty easy to foresee, especially in Southern California. (“It’ll be sunny until the sky darkens, which we’re going to call ‘no longer daytime.’ Back to you in the studio.”)

But even calling the weather there is no longer a slam-drench. Having lived in Los Angeles County from 1958-1976, I think the region gets unfairly dissed about the sameness of its weather. For example, it really does drizzle down there for a few moments each year—except when it STORMS. This happens every other year or so, and it does so with Biblical intensity. Mansions above Malibu—the ones that had been so lovingly rebuilt by the entertainment industry executives who own them after being destroyed semi-annually by wildfires—are swept down the mountain, across Pacific Coast Highway and out to sea. I’m sure it puzzles castaways on uncharted islands who look upon one day and see a 2007 faux-Tuscany villa floating their way.

I might add that among the hordes of tourists who come to Malibu to see the remains of this destruction, nary a damp eye may be found.

Maybe there’s an unwritten law among newscasters, or the consultants who train them, to never apologize the day after your predictions have proved thoroughly wrong. I know there’s one guy in Sacramento who forecasted an actual tornado touching down in California’s capital some time ago. It never happened but, in anticipation of its arrival, caused most of the populace to rapidly learn what hatches were and what it meant to batten them down.

The next day, the no-longer ominous, no-longer ebony-colored clouds passed overhead around 5 a.m. The sun burst through. In a rare moment, I happened to be awake and flipped on the sunrise news: there was a different weather person at that hour, but no mention of the climatic bullet just dodged. That afternoon and evening, when Mr. Fire-and-Brimstone took up his perch in the studio, he talked about the weather that day, what it would be like tomorrow (the jury was now out on that one) but said absolutely nothing about his Henny Penny prediction that the sky had been about to fall only hours before.

Ed Goldman's column appears almost every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. A former daily columnist for the Sacramento Business Journal, as well as monthly columnist for Sacramento Magazine and Comstock’s Business Magazine, he’s the author of five books, two plays and one musical (so far).